Calculating a bond length using moments of inertia

Contents

Calculating a bond length using moments of inertia#

15.6 Bond length#

In calculating a molecule’s moment of inertia, or other properties, first decide where the coordinate origin is going to be, and in what direction the axes are going to point. Data from an X-ray structure already has coordinates defined for us and usually these would be used. With an arbitrary molecule, for instance CO\(_2\), we have to decide which atom is going to be at zero coordinate or perhaps we want to define zero between atoms; it really does not matter as long as each of the atom’s coordinates are relative to zero. Calculating the moment of inertia of a molecule is equivalent to finding its angular momentum, and this could point in any direction but it always passes through the centre of mass. This might therefore be used as the coordinate zero but it is often not convenient to do this unless the molecule is highly symmetrical.

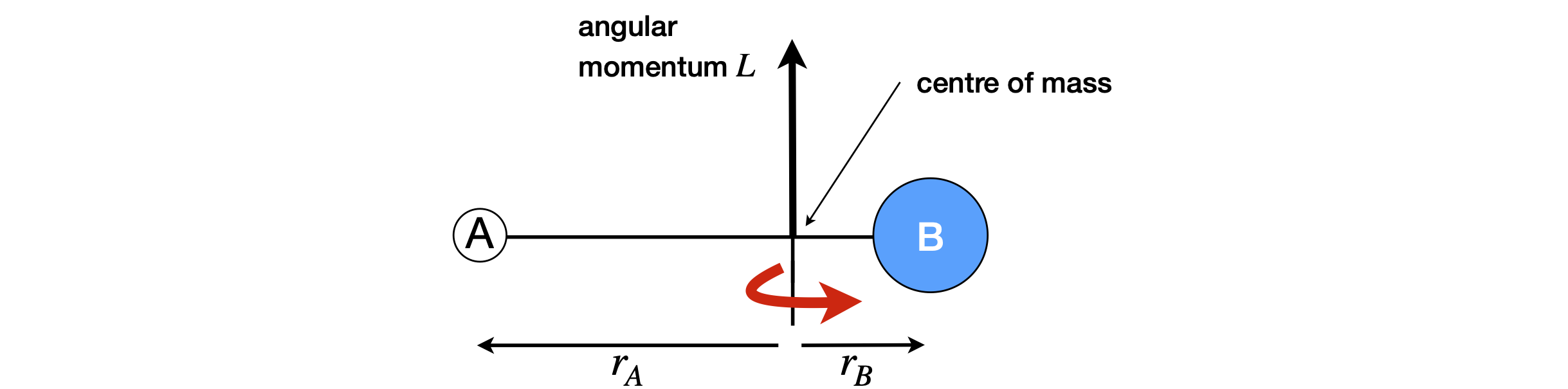

The angular momentum vector

of a typical diatomic molecule is shown in Figure 69, where mass B is heavier than A, as the centre of mass indicates, and \(r\) is the bond length and is equal to \(r = r_A + r_B\). As we have defined the distances \(r_A\) and \(r_B\) from the centre of mass, we have implicitly assumed that this is at zero. The angular momentum passes through the centre of mass, and points in the direction shown if the molecule is rotating perpendicularly to the page, with atom B going into and A coming out of the page. The molecule, if we could view it, would appear to be oscillating as it rotates around an invisible point in space, not centred exactly in the middle of the atoms. The same effect would be seen if you threw a heavy club hammer by its handle to make it spin; the handle rotates around the massive head that hardly appears to move. Any object, with sufficient effort, can be made to spin in any arbitrary direction, but we can always reduce this motion to a combination of contributions on three orthogonal directions we call the principal axes. A molecule or atom, expresses the laws of quantum mechanics far more than macroscopic bodies do and so have only limited values and directions in which the angular momentum can exist. The angular momentum properties are dealt with in detail in most textbooks on quantum mechanics. We will assume that our molecules behave classically.

Figure 69. A sketch showing the direction of one component of the angular momentum of a diatomic molecule. The angular momentum on the internuclear axis is zero.

The angular momentum along the line of the atoms, Figure 69, is essentially zero, because the molecule is linear and the atoms have infinitesimal, effectively zero, dimensions. The molecule also has clockwise or anticlockwise rotation in the plane of the figure with angular momentum pointing directly into, or directly out of the page, respectively. By symmetry, this motion has the same angular momentum as shown in the figure. To calculate bond length \(r\) starting with the moment of inertia, we use the centre of mass formula, equation 71. Put the bond along the x-axis, and the centre of mass at \(x = 0\), then

which produces \(m_Ar_A = m_Br_B\) and relates masses and distances. Equivalently, the turning moments about the centre of mass must be equal, also giving \(m_A r_A = m_B r_B\). The moment of inertia is by definition,

and from these equations, \(r_A\) and \(r_B\) must be removed and replaced with the bond length \(r=r_A+r_B\). Substituting \(r_A\) into \(r=r_A +r_B\) gives \(r=(m_B/m_A +1)r_B\), and for \(r_B\) gives \(r = (m_A/m_B + 1)r_A\).

Next replace \(r_A,\, r_B\) and calculate the moment of inertia

Rearranging and simplifying produces

where \(\displaystyle \mu=\frac{m_Am_B}{m_A+m_B}\) is the reduced mass.

The masses of the atoms are known, hence the bond lengths can be calculated using a measured spectroscopic rotational constant \(B\), and the formula \(\displaystyle B=\frac{1}{100hc}\frac{\hbar^2}{2I}\,\mathrm{cm^{-1}}\). In small molecules, by using laser or microwave spectroscopy, bond lengths can be obtained with extraordinary precision, typically to 0.001 nm. In CO\(_2\) the bond length for the lowest vibrational level is 0.1162 nm, in HCN the CH bond is 0.1066 and the CN bond 0.1153 nm long. Note, however, that the experimental result is more complex, but therefore also more interesting. For example, centrifugal effects cause the bond to stretch as rotational energy is in- creased, and the bond length also increases with vibrational energy. More subtle is the fact that the experimental measurement is \(B\) and what this actually measures is the average \(\langle1/r^2\rangle\), not \(r\) directly. These effects and their resolution are discussed in many books on spectroscopy. It is clear also that for larger molecules, the moment of inertia calculation is going to be very complicated with lots of simultaneous equations, and for these calculations, a matrix method is required. This method, while a little complicated to start with, makes the calculation of the moments of inertia hardly any more difficult for any molecule, irrespective of size, than that just worked through for the diatomic.