Questions 49 - 52

Contents

Questions 49 - 52#

Q49 Superposition of wavefunctions#

Make a superposition of the third and fourth wavefunctions of a particle in a one-dimensional box where the amount of \(\psi_3\) is \(1/2\) and \(\psi_4\) is \(2/5\). Use the wavefunctions \(\displaystyle \psi_n(x)=\sqrt{\frac{2}{L}}\sin\left(n\pi\frac{ x}{L}\right)\) where \(n=1,2,3\cdots\) and L is the length of the box. The energy of the \(n\)th level is \(\displaystyle E_n=\frac{1}{8m}\left(\frac{nh}{L}\right)^2\).

(a) Calculate the period of the oscillation.

(b) The change in probability \(P(x, t)\) over a period of one cycle.

(c) Check your results with python and plot the probability at several times over a period if the box is \(1\) nm in length and \(m\) is the mass of an electron.

Q50 Vibrational wavepacket#

A vibrational wavepacket is the coherent sum of many wavefunctions, and can be made by exciting a molecule into an excited state from the ground state with a laser pulse of femtosecond duration. If the pulse is short \(\approx 10\) fs, it excites many of the vibrational energy levels at effectively the same time. The amount excited depends on the central wavelength, the wavelength spread of the laser pulse, and the Franck-Condon factors. As an electronic transition occurs in a time far shorter than a vibrational period, the molecules must be excited at a similar internuclear extension as determined by the uncertainty limit. The wavepacket is created coherently in two senses; all the molecules are excited at approximately the same time, limited by laser pulse duration, and at the same position on the potential.

The wavepacket \(\Psi\) depends on \(x\) the bond extension and time \(t\). It depends on extension because the wavefunctions \(\psi\) depend only on \(x\) and on time because a non-stationary state is produced, which is not an eigenstate and this must evolve in time. The wavepacket is the summation of the amplitudes of each wavefunction multiplied by the time or phase factor, which is the exponential term, and is

where \(E_n\) is the energy of the \(n^{th}\) vibrational level and \(a_n\) is the amount of each wavefunction present in the superposition and is the product of the Franck-Condon factor for excitation from the ground state and the amplitude of the electric field of the laser pulse at a given energy.

(a) If the molecule is a harmonic oscillator show that the wavepacket recurs, i.e. returns periodically to the same place in the potential, at times \(t = mT\) where \(m = 0, 1, 2,\cdots\) and \(T = 1/\nu = 2\pi/\omega\) is the period of the vibration with frequency \(\nu \, \mathrm{sec^{-1}}\). (The energy levels can be written in different, but equivalent ways, as \(E_n = \hbar \omega(n + 1/2) = h\nu(n + 1/2) = hc\bar \nu(n + 1/2)\) with \(\omega = 2\pi\nu\) where \(\omega\) has units of radian s-1 and \(\bar \nu\) wavenumbers.)

(b) Using the definitions of the harmonic oscillator wavefunctions and using vibrational levels \(n = 0, 1, 2, 3, 4\) with \(a_n = [0.1, 0.2, 0.25, 0.2, 0.1]\) use python to illustrate the wavepacket motion and confirm the recurrences.

Use numerical values for HI, which has vibrational frequency \(\bar \nu = 2309.5 \,\mathrm{cm^{-1}}\). The harmonic oscillator wavefunction \(\psi\) at extension \(x\) and quantum number \(n\) is \(\displaystyle \psi_n(x) = N_nH_n(x\sqrt{\alpha})e^{ -\alpha x^2/2}\) where the normalisation is \(\displaystyle N_n =(\alpha/\pi)^{1/4}(2^nn!)^{-1/2}, \; \alpha=\sqrt{k\mu}/\hbar\) and \(H\) is the Hermite polynomial, \(k\) the force constant and \(\mu\) the reduced mass.

Strategy: In (a) do not try to solve the wavepacket equation but show that it is the same at times \(mT\) as it was at time zero. A good starting point would therefore seem to be to substitute for the energy and then time into equation (55) and rearrange the resulting equation.

Q51 Rydberg atom#

As the energy of an H atom increases, the energy levels become closer together because \(E_n = R/n^2\) where \(R\) is the Rydberg constant and \(n\) the principal quantum number. Exciting an H atom from the ground state into a level close to the dissociation limit with a picosecond laser excites many levels virtually simultaneously compared to the classical orbital period of these levels, and a wavepacket is produced. If the atom is optically excited from the ground state s orbital with \(\ell = 0\), the wavepacket is a sum of the radial distributions of the p or \(\ell = 1\) electronic wavefunctions with different principal quantum numbers. The electron is promoted to a higher energy orbital, which has a large orbital radius; the many similar wavefunctions add up to generate a wavepacket whose amplitude increases and decreases, and gives the appearance that the electron orbits the nucleus.

(a) Calculate and plot the radial distribution of the wavepacket produced as time vs position.

(b) Comment on the size of the wavepacket and its period of the motion compared to that with \(n = 1\). The oscillation frequency is given by \(\displaystyle \omega =\hbar^{-1}|dE_n/dn|\) and the absolute value is taken only to make the frequency positive.

Assume that the laser’s energy is such that the central wavelength excites the levels with \(n = 40\), and five levels are excited either side of this, and the laser excites these levels with amounts \(0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.5, 0.8, 1, 0.8, 0.5, 0.3, 0.2, 0.1\). (Different amounts would be used depending on an actual laser’s pulse duration and shape but this list corresponds very approximately to a Gaussian shaped pulse of \(1/2\) ps duration.)

Strategy: Look up the equations for the radial distribution functions of the H atom. The associated Laguerre polynomial is involved which can be calculated explicitly, but there is a built-in function in scipy/numpy/python,(scipy.special.eval_genlaguerre(n,\(\alpha\),x)) which provides a rapid and accurate way of calculating this function.

Q52 Quantum beats#

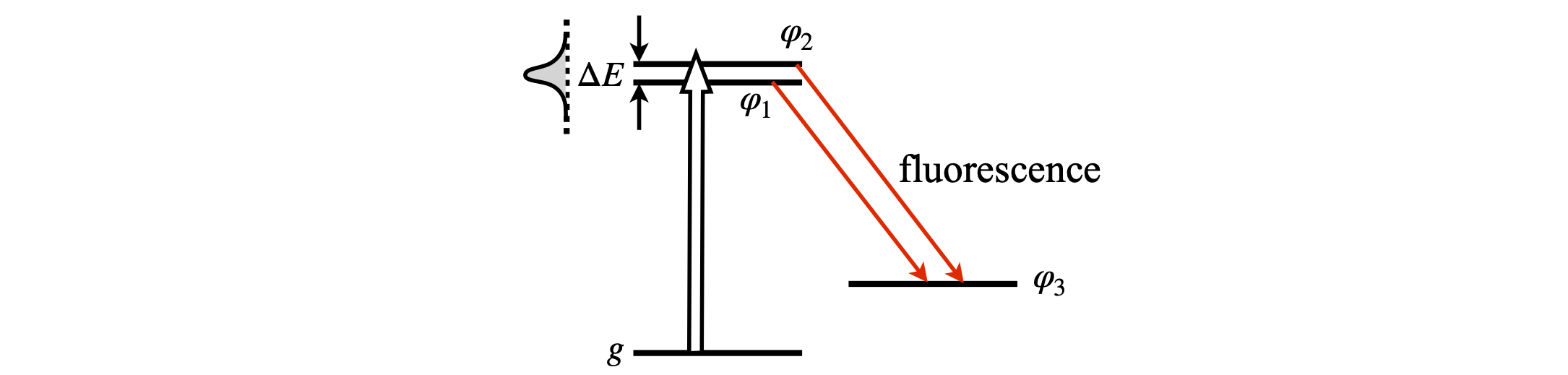

When two or more atomic or molecular eigenstates are coherently excited into an electronically excited state, for example by a laser pulse, and their total emission to a common ground state measured, quantum beats may be observed as oscillations in the total fluorescence. In the experiment three states are involved, see Fig. 17. The beat frequencies directly measure the energy splitting \(\Delta E\) in pairs of excited levels. This experiment is a very good way of measuring small energy gaps between levels, because small gaps produce long beat periods that are easily measured in a time-resolved experiment and this, therefore, can be a good way of doing high-resolution molecular spectroscopy.

Figure 17. Quantum beat spectroscopy. Two levels are excited from a vibrational level \(g\) in the ground state to the first excited electronic state and their total fluorescence decay from excited levels 1-3 and 2-3 to a common state is measured.

The fluorescence signal is given by

where \(\varphi_3\) is the wavefunction of the final state and \(\psi(t)\) the superposition state (wavepacket) excited by the laser. This is made up from the two states \(\varphi_1\) and \(\varphi_2\), and \(\mu\) is the dipole moment operator coupling excited state levels \(1\) and \(2\) to final state ground state level \(3\). The integral is over a spatial dimension \(q\) of the wavefunction, such as a bond extension. The constant \(beta\) consists of instrumental parameters. The laser pulse exciting the states is long compared to the vibrational period, so that position is averaged out in these experiments; this is why there is the integration over bond extension \(q\). The interference leading to beats arises from the fact that two pathways, \(1\to 3\) and \(2\to 3\), see Fig.17, are simultaneously measured and in quantum processes one path cannot be distinguished from the other when both fluorescence wavelengths are measured at the same time. The signal is always the square of the sum of the amplitudes of each contribution. The superposition of the two states populated with the laser is the wavepacket

and as both levels fluoresce with the same rate constant \(k\), then this equation can be changed to

(a) Calculate the decaying fluorescence signal if the decay rate constant has the same value k from each level excited. Assume that the integrals are \(\displaystyle \int \varphi_3\,\mu\,\varphi_1dq=B_{31}\) and \(\displaystyle \int\varphi_3\,\mu\,\varphi_2dq = B_{32}\).

(b) Normalize the signal at \(t = 0\).

(c) Plot a graph of the normalized signal if \(k = 1\,\mathrm{ ns^{-1}}\) and \(\Delta E = 1\,\mathrm{ cm^{-1}}\) and the laser produces levels with amounts \(a_1 = 0.3\) and \(a_2 = 0.7\) and \(B_{32} =B_{31} = 2\).

(d) Fourier transform signal to find the energy separation between levels.

(e) Repeat the calculation with with four levels with energies above the lowest level of \(1, 2\), and \(3\,\mathrm{ cm^{-1}}\) excited with amounts \(0.3, 0.7, 0.3\), and \(0.7\). Assume that the other parameters are the same as above. Plot the graph of the decaying signal. Fourier transform it to find the frequencies present.