15 Moments of Inertia

Contents

15 Moments of Inertia#

Introduction#

Angular momentum plays a central role in chemistry, but this is usually in the context of nuclear and electron spin; for example, nuclear spin gives rise to NMR and electron spin (EPR) spectroscopies, as well as being essential for the formation of the chemical bond. The rotation of whole molecules is a natural consequence of thermal motion and is observed with microwave, infrared, Terahertz, or Raman spectroscopy. These techniques are used to measure the spacing between a molecule’s rotational energy levels. This is described next, followed by a brief description of angular momentum and moments of inertia. Finally, the calculation of bond lengths is described.

15.1 The rotational motion of molecules#

The collision between molecules in the gas phase and at the prevailing temperature equilibrates the energy among translation, vibration, and rotational motions. A molecule can only have discrete values of vibrational or rotational energy. The lowest rotational energy is zero, and the energy levels become more widely spaced as the quantum number \(J\) is increased. The equation

describes the rotational energy, in joules, of a (rigid rotor) diatomic or linear molecule, with quantum number \(J = 0, 1, 2, \cdots\). The multiplicity and also degeneracy of a rotational level with quantum number \(J\), is \(g_J = 2J + 1\). The constant \(I\) is the moment of inertia, and is typically \(\approx10^{-45}\;\mathrm{kg\,m^2}\) for a molecule. It is this small, because a molecule’s mass is small, and its bond lengths short. An apple has a value \(I \approx 10^{-4}\;\mathrm{kg\,m^2}\) and a lorry’s wheel \(\approx 10\;\mathrm{kg\,m^2}\). As we shall see the moment of inertia is related to a bond length.

A rotational constant is defined as \(B=\frac{\hbar^2}{2I}\) making the energy \(E_J=BJ(J+1)\). Remembering that a joule is a unit of energy with base units of mass \(\times\) velocity squared, the constant \(B\) has units

Usually, however, \(B\) is expressed in units of wavenumbers (cm\(^{-1}\)) produced by dividing \(B\) by \(100hc\); the factor \(100c\) is used because \(c\) has units of m s\(^{-1}\) and we want units in cm\(^{-1}\); \(\displaystyle B=\frac{1}{100hc}\frac{\hbar^2}{2I}\).

The rotational constant \(B\) has a value that is typically less than a wavenumber. Its largest value, \(\approx 64 \;\mathrm{cm^{-1}}\), is for H\(_2\), but clearly this is not typical, as this is the lightest molecule. Once the rotational spectrum is measured, it is easy to measure \(B\), because the lines (in a diatomic ) are spaced by \(2B\). In real molecules, things are more complex, because of centrifugal distortion in the rotating molecule, but this effect is small for low \(J\) quantum numbers and does not fundamentally change our analysis. The last step is to calculate the bond length from \(I\). At one time, this was the main purpose of microwave spectroscopy, but nowadays, bond lengths of very many small molecules have been accurately measured. The technique is now more often used analytically, for example, to identify species in interstellar dust clouds, or to monitor the ethene produced by ripening fruit.

15.2 Angular momentum and moment of inertia#

The angular momentum of a solid body is the momentum caused by virtue of its rotational motion and is a vector quantity. In an isolated molecule, this motion is about the centre of mass, also called the centre of gravity. The angular momentum produced has a fixed direction in space. In general, it is just as possible to cause the rotational motion of an object to be about its end as it is about its middle. A rod can be spun about its centre, along its axis, or about its end, and each angular momentum will be different. If the body rotates with angular frequency {, the angular momentum \(\pmb{L}\) is given by \(\pmb{L} = \pmb{I\omega}\), where \(\pmb{I}\) is a matrix of moment of inertia values and \(\pmb{L}\) and { are one-dimensional matrices or vectors. The reason for the vector quantities is that a body can move in three dimensions and the motion can be split into components along three axes. The moment of inertia of (rigidly connected) masses, where each has mass \(m_i\), is \(I = \sum_i m_ir_i^2\) where \(r_i\) is the perpendicular distance of mass \(i\) from an axis. In fact, we can choose the axes to be anywhere we want so the moment of inertia depends on where these axes are placed; it is therefore not a fundamental property of an object. This presents a problem if we are to try to calculate bond lengths, because different values would be obtained depending on where the axes are placed. The obvious place is to locate the axes at the centre of mass since a freely rotating object will rotate about this point. However, in what directions the axes point relative to the molecule has still to be chosen. Very often, we may choose to align the axes with some symmetry axis of the molecule. The molecule will always rotate about its own inertial axes and if these two sets of axes do not coincide, and they usually do not, the moments of inertia will have the form of a matrix with terms that depend on where an atom is with respect to any two axes, \(I_{xy}, I_{yz}\) etc. All is not lost, however, because there is a simple way to rotate our chosen axes onto the molecule’s inertial axes, making the moment of inertia matrix, diagonal. This will be described in Section 15.8.

The total kinetic energy of a rigid body is that due to its linear plus rotational energy. The linear kinetic energy is

and the rotational kinetic energy

thus, the moment of inertia \(I\), takes the place of the mass used to describe linear motion and angular velocity \(\omega\) (radians s\(^{-1}\)), replaces linear velocity \(\pmb{v}\) in m s\(^{-1}\). Similarly, linear momentum \(\pmb{p}= m\pmb{v}\), is replaced by angular momentum \(\pmb{L} = I\pmb{\omega}\), which is also vector quantity. The angular momentum relative to the centre of mass about an axis at the centre of a rigid disc of mass \(m\), is shown in Figure 53 and is \(\pmb{L}= m \pmb{r}\times \pmb{v}\) where \(\pmb{v}\) is the velocity of the edge of the disc and \(\pmb{r}\) its radius vector. The angular momentum points in the direction away from you, if the disc rotates clockwise when you look at its underside.

Angular velocity is, by definition, the rate of change of the angle \(\theta\) the rigid body moves through, and has units of radians / second. It can be shown that the velocity vector \(\pmb{v}\) in the centre-of-mass coordinate system is related to the angular velocity \(\pmb{\omega}\) as

The angular momentum becomes \(\pmb{L} = m\pmb{r} \times \pmb{\omega} \times\pmb{r}\), and evaluating the cross product the angular momentum is

where \(I\pmb{ }\)is a \(3 \times 3\) matrix of the moment of inertia components. The equation can be written as

where \(I_{xy}=I_{yx} \) etc. Calculating each of these terms is described in Section 13.4. The angular momentum is always proportional to the angular velocity; the proportionality is the moment of inertia, and hence the emphasis falls on calculating this. Sometimes, the angular momentum matrix is called the angular momentum tensor.

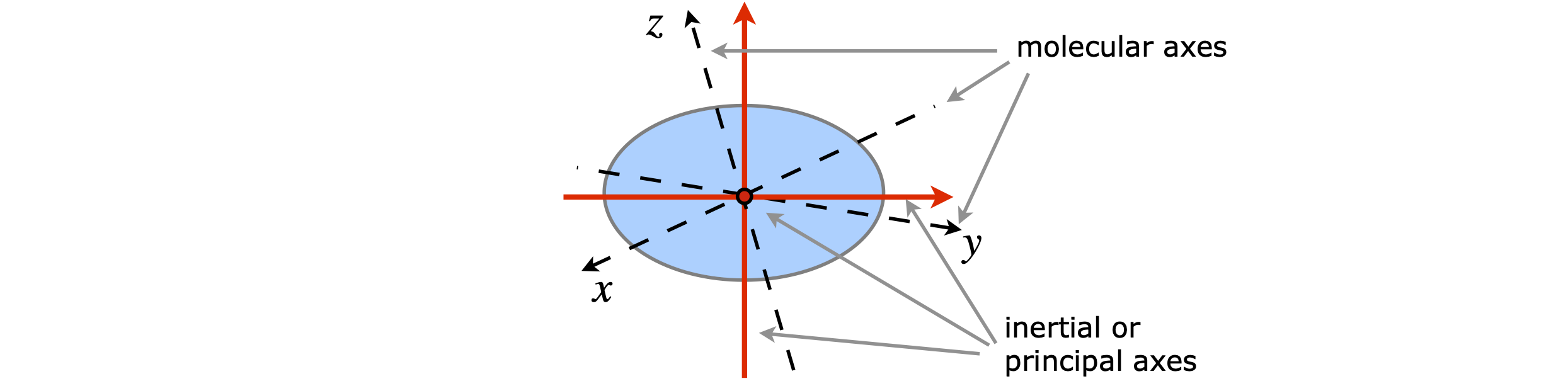

To summarize: A molecule or other solid object will rotate about its own inertial (principal) axes that are fixed in space. The geometrical axes we chose to place on the molecule need not be coincident with the inertial axes, in fact, they are usually not, and therefore the inertial matrix has off-diagonal elements. Should the inertial and geometrical axes coincide, only the diagonal values exist. By diagonalizing the inertial matrix, the two sets of axes are made coincident, and the diagonal moments of inertia of the principal or inertial axes can be calculated.

Figure 66. The dashed lines represent the molecular axes,i.e. those axes which make sense when looking at the molecules structure; the solid lines the principal axes obtained after diagonalizing the moment of inertia matrix, the third axis of which is perpendicular to the page and shown as a circle. The ellipse represents a molecule.

15.3 Solid bodies#

If the rotating body is not made of discrete parts such as a molecule is, then integration over the mass and distances must be done instead of summation. The summation is replaced by an integral; some examples are given in Chapter 4.8.2 and 4.10.1. The moments of inertia have been worked out for very many geometrical objects, cones, cylinders and so forth and lists can usually be found in engineering textbooks.

15.4 Discrete bodies: molecules#

The moment of inertia is not an intrinsic property of a body but depends upon the axis about which the moment is taken. In chemical physics, it is usual to make this axis pass through the centre of mass. In engineering, the moment of inertia about some remote axis may be needed instead. By the principle of parallel axes; if the moment of inertia with reference to an axis through its centre of mass \(I_{cm}\) is known, it can easily be changed to a value about a parallel axis \(I_p\) if the parallel axis is a distance \(d\) away. The result is

where \(M\) is the total mass.

The moment of inertia of a collection of atoms is defined as the summation of the product of the mass and the distance squared from an axis \(\alpha\) through the centre of mass,

where \(r_i\) is the distance of mass \(i\) from the axis \(\alpha\) passing through the centre of mass. As the mass (atom) has coordinates \((x, y, z)\), and \(r\) is the distance given by Pythagoras, for example, from the \(x\)-axis, \(r =\sqrt{(z - z_{cm})^2 + (y - y_{cm})^2}\) where \(z_{cm}\) and \(y_{cm}\) are the coordinate of the centre of mass, and similarly, for the \(y\)- and \(z\)-axes. The centre of mass of \(i\) masses is defined as

where \(q\) can be \(x, y\), or \(z\) and \(M\) is the total mass. The moment of inertia about the \(x-, y-\), or \(z\)-axes whose origin is at the centre of mass, is

The total moment of inertia is

where \(r_i\) is the distance of mass \(m_i\) from the centre of mass.

A planar object, such as a sheet or loop of wire in the \(x - y\) plane, with \(z\) being perpendicular to these has moments

therefore

This is true only for planar bodies or uniform composition (lamina) and is called the Perpendicular Axis Theorem.

The moment of inertia can also be defined as

where \(R_g=\sqrt{I_\alpha /M }\)is called the radius of gyration of the body about axis \(\alpha\) and \(k\) is the root mean square radius from the axis.