Solutions Q25 - 32

Contents

Solutions Q25 - 32#

# import all python add-ons etc that will be needed later on

%matplotlib inline

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from sympy import *

init_printing() # allows printing of SymPy results in typeset maths format

plt.rcParams.update({'font.size': 16}) # set font size for plots

Q25 answer#

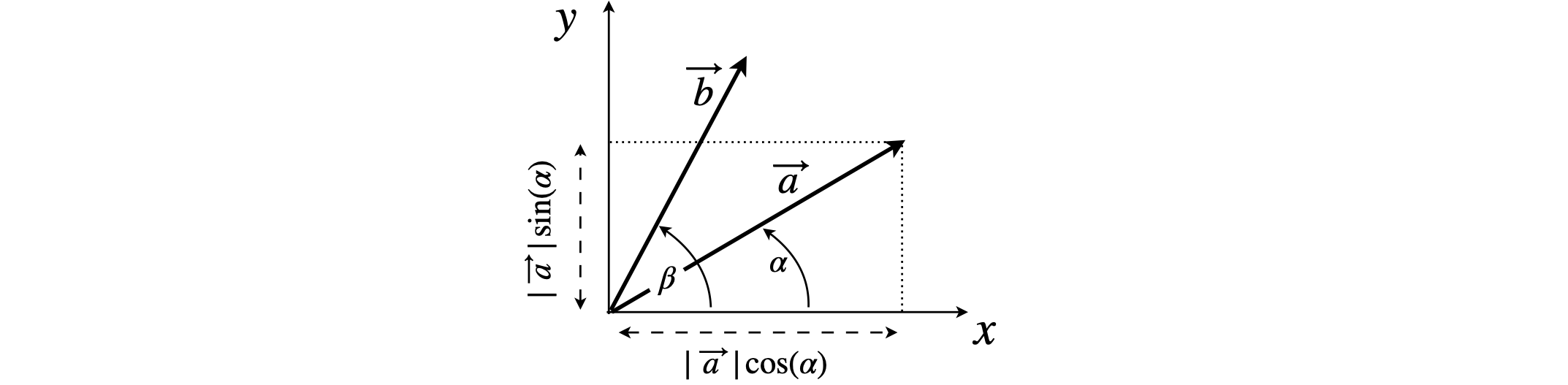

(a) The vector \(\vec a\) and its projections onto the \(x\)- and \(y\)-axes are shown in figure 68. If \(\boldsymbol i\) and \(\boldsymbol j\) are unit vectors along the \(x\)- and \(y\)-axes, and as \(\vec a\) is described in the question as a unit vector, its length must be \(| \vec a | = 1\).

By definition, vector \(\vec a\) has components which are multiples of the base vectors \(\boldsymbol i\) and \(\boldsymbol j\), and is therefore,

because \(\cos(\alpha)\) is the component on the \(x\)-axis, along which the base vector \(\boldsymbol i\) lies. The component along \(\boldsymbol j\) and the \(y\)-axis is \(\sin(\alpha)\).

Figure 68. Vectors and their projections.

Similarly, vector \(\vec b = \cos(\beta)\;\boldsymbol i + \sin(\beta)\;\boldsymbol j\). Their dot product is

because \(\boldsymbol i\cdot\boldsymbol i = \boldsymbol j\cdot\boldsymbol j = 1\) and \(\boldsymbol i\cdot\boldsymbol j = 0\). From the diagram, the angle between the two vectors is \(\beta - \alpha\), therefore the dot product is

again using the fact that \(\vec a\) and \(\vec b\) are unit vectors. Therefore, by equating the two dot product equations, the trigonometric identity is found:

Suppose that vector \(\vec b\) is changed, so that it points downwards in the figure making its angle \(-\beta\) to the x-axis, then the angle between the vectors becomes \(\alpha + \beta\) and \(\vec b = \cos(-\beta)\;\boldsymbol i + \sin(-\beta)\;\boldsymbol j = \cos(\beta)\;\boldsymbol i - \sin(\beta)\;\boldsymbol j\) therefore

(b) Repeating the first part of the calculation in matrix - vector form, the two vectors are

the dot product of which is a little easier to calculate than \(ijk\) vectors, viz,

Q26 answer#

(a) Adding together base vectors to form the \(x\) and \(y\) orbitals, and forming the dot product in matrix vector form, gives

therefore the orbitals are orthogonal and they are also normalized because

and similarly for \(\psi_{2p_y}\).

(b) If orthogonal, the dot product should be zero. It will contain nine terms

The product can be expanded out term by term and then the orthogonality of the base vectors used. This means that only \(\vec \psi_{p_{+1}}\vec\psi_{p_{+1}}\) etc are not zero; hence the dot product is zero and these orbitals are orthogonal.

Alternatively, the orbitals can be represented as combinations of base vectors in the basis set of \((s, p_{+1} , p_{-1})\) orbitals:

The orthogonality test for \(p_1\) with \(p_x\) and \(p_y\) is

so neither \(p_x\) nor \(p_y\) are orthogonal to the \(p_1\) orbital. The same is true of the \(p_2\) orbital. They would therefore not be of much use to study molecular properties.

(c) The wavefunctions \(\psi_s, \psi_{p_x}, \psi_z\) are orthogonal to one another, and this makes the calculation easy. A basis set of these orbitals in the order, \((s, x, z)\) can be used. The \(+xy\) and \(-xy\) orbitals are orthogonal as shown by the dot product calculation;

The similar calculation with the other orbitals shows that they are orthogonal to one another. The hybrid orbitals are not orthogonal to the \(p_x\) or \(p_y\) orbitals. The \(p_x\) is represented with the vector \(\begin{bmatrix}0 &1& 0\end{bmatrix}\) in the \((s, p_x, p_y)\) basis set. The \(p_z\) orbital is orthogonal to both the \(±\pm xy\) orbitals. This can be understood because there is no \(z\) component in these orbitals. By forming a basis set in \((s, p_x, p_y, p_z)\) the \(xy\) orbitals will have a zero component for \(p_z\), the \(p_z\) orbital has \(1\) here and zero elsewhere, therefore the dot product zero, e.g.

If you are not convinced, then the hybrid orbitals can be broken down into the \(p_z, p_{+1}, p_{-1}\) orbitals and the calculation repeated.

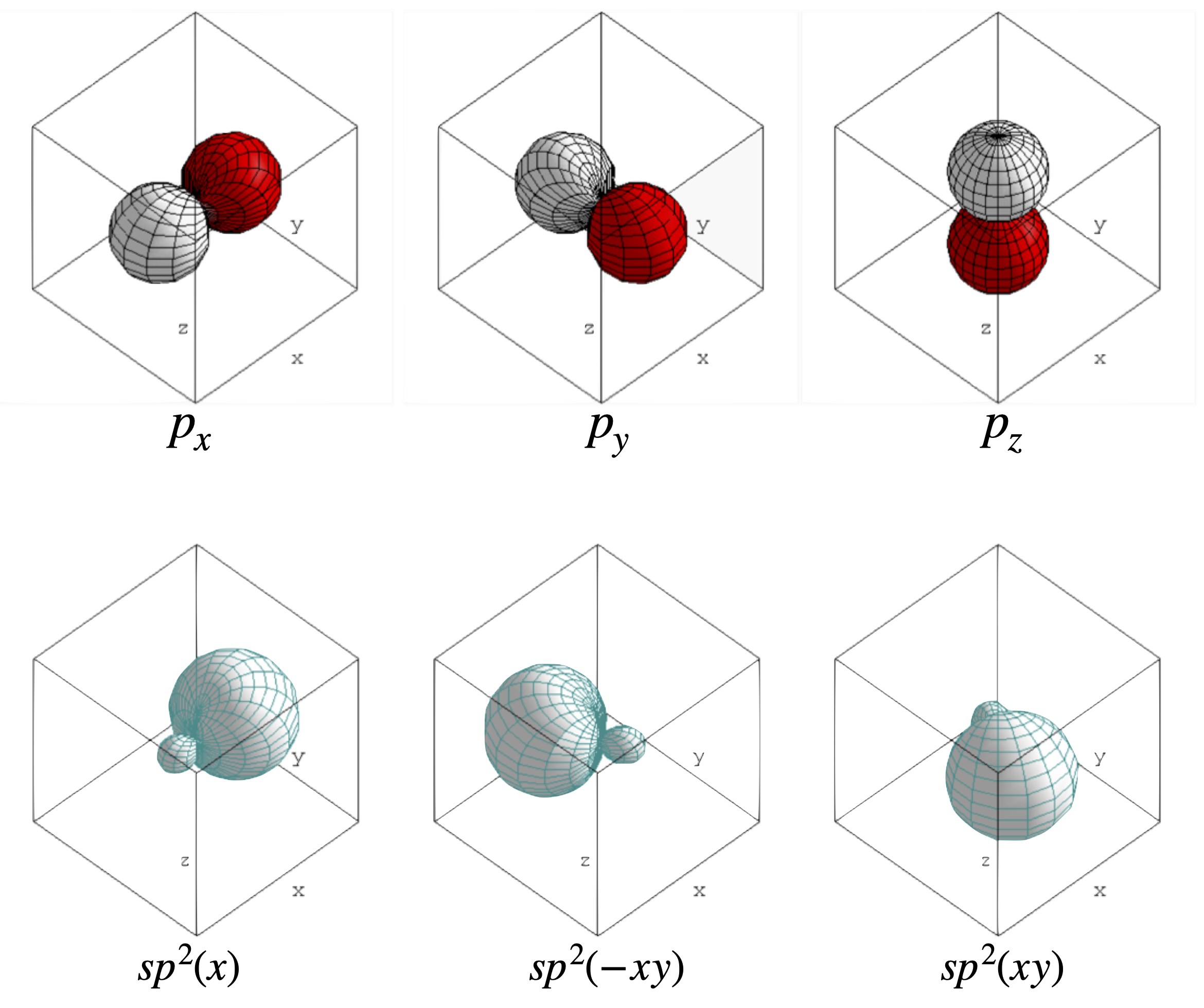

(d) The \(p_x, p_y\) and \(p_z\) orbitals are shown in figure 69, and the np\(^2\) hybrid orbitals, which lie at \(120^\text{o}\) to one another in the \(x-y\) plane as expected for the sp\(^2\) hybridization of \(p\) orbitals.

Figure 69. The \(2p\) orbitals (top) and the sp\(^2\) hybrids (bottom).

(e) To test for orthogonality of the base orbitals \(p_0\) and \(p_{+1}\), the calculation is

The \(\varphi\) integration is separated out because there is no term in both \(\varphi\) and \(\theta\). Both integrations are easy when transformed to exponential form but that in \(\varphi\) can be seen because \(e^0=1\), as does \(e^{2\pi i}\) and so this integral is the same at both limits and hence zero. The same result is obtained for the \(p_0\) and \(p_{-1}\) orbital.

Normalization for the \(p_{+1}\) orbital is

and the same integration occurs for \(p{-1}\) as the \(\varphi\) term disappears with the complex conjugate. The \(\theta\) integral can be simplified by converting to the exponential form, or by using \(\sin^3(\theta) = (3\sin(\theta) - \sin(3\theta))/4\).

Q27 answer#

(a) The dot product is \(\displaystyle\begin{bmatrix} 1&1&1&1\end{bmatrix}\begin{bmatrix} 1\\1\\-1\\-1\end{bmatrix}=0\) that the vectors are orthogonal.

(b) The \(s\) orbital has spherical symmetry; the dot product of the \(p\) orbitals is \(\displaystyle \frac{1}{3}\begin{bmatrix} 1&1&1\end{bmatrix}\begin{bmatrix} 1\\-1\\-1\end{bmatrix}=-\frac{1}{3}\) where the \(3\) normalises. From this result \(\cos(\theta) = -1/3\), making the angle \(109.47^\text{o}\).

Q28 answer#

In this example, the s-orbital \(\psi_s\) is spherically symmetric and cannot affect in which direction the hybrid orbitals point and we need not include it in the calculation. Comparing the orbital coefficients \(b=-1/\sqrt{6},\quad c=\sqrt{3}/\sqrt{ 6}=1/\sqrt{2};\quad d=0\) because there is no \(\psi_{p_z}\) wavefunction included in \(\psi_1\), and for \(\psi_2\), \(b=-1/\sqrt{6},\quad c=-1/\sqrt{2};\quad d=0\).

With these coefficients, two vectors can be made,

and the \(s\) orbital is ignored. The angle between them is found from the dot product \(\vec v_1\cdot \vec v_2 = |\vec v_1 ||\vec v_2 |\cos(\theta)\) and using equation 2, \(\cos(\theta)=-1/2\) or \(\theta =120^\text{o}\) so it seems reasonable that \(\psi_1\) and \(\psi_2\) represent sp\(^2\) hybrid orbitals. If we did include the \(s\) orbitals in a basis set of four elements, the \(s\) and three \(p\) orbitals, then these vectors are orthogonal which they have to be for any eigenfunctions that are solution of the Schroedinger equation,

(c) Substituting for the \(p_{\pm 1}\) orbitals gives

Their dot product is found using the coefficients

therefore, these orbitals are orthogonal. To calculate the angle, the \(s\) orbital part has to be ignored and the calculation repeated, remembering to re-normalize the vector, as it is now only two dimensional. In this case, the dot product is \(-1/2\) and the angle \(120^\text{o}\). This confirms that sp\(^{2}\) hybridization is involved as found in part (b).

(d) The principal quantum number \(n=2\), is good for all orbitals as only \(2p\) or \(2s\) orbitals are involved. The \(p_x, p_y, p_1\) and \(p_2\), have undefined \(m\) quantum numbers because they are hybrids of different base orbitals with different \(m\) quantum numbers. The \(p_1\) and \(p_2\) orbitals are \(s-p\) hybrids so that quantum number \(l\) is also undefined.

Q29 answer#

(a) The body-centred cell: assuming,for simplicity,that the cube has length \(1\), then by inspecting the body-centred cube the vectors to the points are

In row matrix form \( \vec{oa}=\begin{bmatrix}1/2 &1/2 &1/2\end{bmatrix},\; \vec{ob}=\begin{bmatrix}0 &0& 1\end{bmatrix}\).

The distance \(a \to b\) is calculated by forming a vector \(\vec{ab}\) and finding its length; this vector is \(\vec{ab} = \vec{ob} - \vec{oa} = -\boldsymbol i/2 - \boldsymbol j/2 + \boldsymbol k/2\) with length \(\sqrt{\boldsymbol i\cdot \boldsymbol i/4-\boldsymbol j\cdot\boldsymbol j/4+\boldsymbol k\cdot\boldsymbol k/4}=\sqrt{3/4}\) or \(q\sqrt{3/4}\) by accounting for the true size of a side.

(i) Angle \(\angle bac\): by geometry the length \(ac\) has to be the same as \(ab\), but to find the angle \(\angle bac\) we need the vector \(\vec ca\), which is \(\vec{oc} - \vec{oa} = +\boldsymbol i/2 -\boldsymbol j/2 -\boldsymbol k/2\). The angle is calculated using

and therefore the angle \(\angle bac = 109.47^\text{o}\). In matrix form this calculation is

The angle \(\angle bac\) is the same as in a tetrahedron, which is to be expected as a tetrahedron can fit inside a cube with vertices at opposite corners and across a diagonal.

(ii) The angle \(\angle bad\) is found from the dot product of \(\vec{ad}\) with \(\vec{ab}\). Vector \(\vec{ad}\) is \(\vec{od}-\vec{oa}=2\;\boldsymbol i-\boldsymbol i/2-\boldsymbol j/2- \boldsymbol k/2=(3i-j-k)/2\) and has a length \(q\sqrt{11/4}\). The angle is calculated as

and the angle \(\angle bae= 121.4^\text{o}\) which is the same as angle \(bad\), as might have been spotted from the symmetry of the atoms.

(b) The Python calculation for the face-centred cube is straightforward, once the matrices to hold the vectors from the origin, \(Oa, Ob\), and so forth are defined. Dot products are used to find the lengths. Once the vectors are set up it is very easy to calculate any length or angle, whereas using geometry and repeatedly using Pythagoras’ Theorem is far harder. If you want to repeat the calculation for the body-centred cube, change the initial vectors.

#--------------------------- # define routine to calculate angle

def get_angle(veca,vecb):

len_veca = np.sqrt( np.dot(veca,veca))

len_vecb = np.sqrt( np.dot(vecb,vecb))

angle = np.arccos(np.dot(veca,vecb)/(len_veca*len_vecb) )*180/np.pi

return angle

#---------------------------

Oa = np.array([1/2, 1 , 1/2]) # use np.array() to make vectors

Ob = np.array([0 , 0 , 1 ])

Oc = np.array([3/2, 0 , 1/2])

Od = np.array([3/2, 1/2, 1 ])

Oe = np.array([2 , 1/2, 1/2])

ab = Ob - Oa # define new vectors

ac = Oc - Oa

ad = Od - Oa

ae = Oe - Oa

print('{:s}{:8.2f}{:s}'.format('angle ab-ac ',get_angle(ab,ac) ,' degrees') )

print('{:s}{:8.2f}{:s}'.format('angle ab-ad ',get_angle(ab,ad) ,' degrees') )

print('{:s}{:8.2f}{:s}'.format('angle ab-ae ',get_angle(ab,ae) ,' degrees') )

angle ab-ac 73.22 degrees

angle ab-ad 80.41 degrees

angle ab-ae 97.42 degrees

Q30 answer#

Starting with the definition \(\vec v = |\vec v|(\cos(\alpha)\;\boldsymbol i + \cos(\beta)\;\boldsymbol j+ \cos(\gamma)\;\boldsymbol k)\),

the dot product of \(\vec v\) with itself is \(\vec v\cdot\vec v = |\vec v|^2(\cos^2(\alpha) + \cos^2(\beta) + \cos^2(\gamma))\)

where the rules \(\boldsymbol i\cdot\;\boldsymbol i = 1\), and \(\boldsymbol i\cdot\;\boldsymbol j = 0\) and so forth, were used. However, a vector is parallel to itself, therefore by definition, \(\vec v\cdot\vec v = |\vec v |^2\cos(0)\) and as \(\cos(0) = 1\) then \(\cos^2(\alpha) + \cos^2(\beta) + \cos^2(\gamma) = 1\).

Q31 answer#

(a) \(\vec A+\vec B=2\;\boldsymbol i+2\;\boldsymbol j+6\;\boldsymbol k\), \(|\vec A|=\sqrt{3}\), \(|\vec B|= \sqrt{35}\), \(\vec A\cdot\vec B=3\), \(\cos(\theta)=\sqrt{3/35}\).

(b) \(\vec A+\vec B=5\;\boldsymbol i- 4\;\boldsymbol j+7\;\boldsymbol k\), \(|\vec A|=\sqrt{26}\), \(|\vec B|=\sqrt{38}\), \(\vec A\cdot\vec B=13\), \(\cos(\theta) = 13/\sqrt{26\cdot 38} = 0.4135\).

(c) \(\vec A+\vec B=2\;\boldsymbol i+\;\boldsymbol j+\;\boldsymbol k\), \(|\vec A|=|\vec B|\sqrt{2}\), \(\vec A\cdot\vec B=1\), \(\cos(\theta)=1/2\).

Q32 answer#

Assume ideal geometries for the molecules,and use symmetry where possible to simplify the calculation, and then add all the vectorial components together. The resultant dipole could point in any direction, so it is necessary to define axes on the molecules, and calculate dipoles along each axis and then form the total. This definition based on symmetry, is effectively a principal axes transformation; see Chapter 7.13.8.

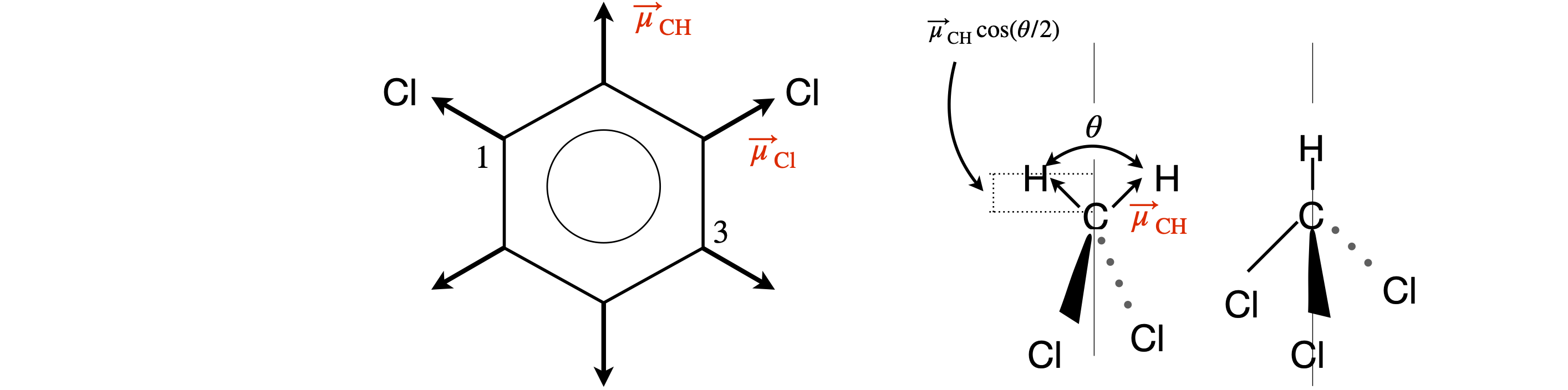

(a) This molecule is flat,and if the \(z-y\) plane is chosen to be the plane of the molecule, there is no z component. In benzene derivatives, each bond dipole is at \(60^\text{o}\) to the next one. If one chlorine atom is at position 1, the angle to the other atom in position 3, is \(120^\text{o}\). Drawing the molecule, shows that if atom 2 is along the y-axis, the molecule has \(C_{2V}\) symmetry (has two mirror planes and a \(C_2\) rotation axis) about this axis, which means that only half the bond dipoles need to be calculated, the total being twice this sum.

Figure 70. Illustrating geometries for dipole moment calculation. The \(z\) and \(y\) are in the plane of the figure, \(x\) points out.

The dipole is a projection of the bond dipoles on the \(z\)-axis, because by symmetry the \(x\) and \(y\) dipole components are zero. Only two Cl and two H atoms are needed, giving a dipole of

(b) In methylene chloride, the two H atoms are at \(90^\text{o}\) to the two Cl atoms because the molecule is tetrahedral. Using the same axes as in part (a), the H atoms are in the \(z-y\) plane and the Cl atoms in the \(z-x\) plane. By symmetry, the dipole component along the \(x\)- and \(y\)-axes is zero. If \(\theta\) is the bond angle, \(\cos^{-1}(-1/3)\), the dipole is the \(z\) component which is

(c) In chloroform,the positions of the chlorine atoms are quite difficult to calculate using geometry and the dipole can more easily be calculated using vectors.

The geometry is tetrahedral, so that the atoms are at positions: carbon \((0, 0, 0)\) and the H and Cl atoms \((R)\) at

The amount of the total dipole along each axis can be found by calculating the dot products with the base vectors \(\vec x=\begin{bmatrix}1&0&0\end{bmatrix},\vec y=\begin{bmatrix}0&1&0\end{bmatrix},\vec z=\begin{bmatrix} 0& 0 & 1 \end{bmatrix}\). The bond dipoles are \(\mu_H\) and \(\mu_{Cl}\) etc.

The total dipole along the x axis is \(\vec \mu_x = \vec x\cdot\vec H\mu_H + \vec x\cdot\vec R_1\mu_{R_1} +\vec x\cdot\vec R_2\mu_{R_2} +\vec x\cdot\vec R_3\mu_{R_3}\) and a similar calculation applies for the \(y\) and \(z\) axes and the vector of the total dipole, \(\vec mu=\mu_x\vec x+\mu_y\vec y+\mu_z\vec z\) of magnitude \(\mu\sqrt{\mu_x^2+\mu_y^2+\mu_z^2}\).

and the same result is found for the \(y\) and \(z\) components. The total dipole is \(\mu_H - \mu_{Cl} = 1.16\) debye. The \(\sqrt{3}\) arises from normalizing the bond vector, because the dot product is used to produce direction cosines. The dipole points along the CH bond because all \(x, y, z\) components are equal, and the H atom is at coordinate \((1, 1, 1)\) and the carbon at the origin.

Repeating part (b) to calculate the dipole for methylene chloride using vectors produces

and \(\mu_y = 0, \mu_z = 2(\mu_H - \mu_{Cl})/\sqrt{3}\) giving a dipole of \(1.34\) D.