Questions 11 - 17

Contents

Questions 11 - 17#

Q11 Heat Capacity#

(a) Calculate the heat capacity as in Figure 14. If you choose a bigger lattice, remember that the time for each calculation increases directly with the total number of sites not the size of the lattice side.

(b) Find the change in magnetization per step, and calculate the magnetization by modifying the code. Reproduce the graph. When making the total magnetization, add the absolute value of the change. Do this, because at low temperatures the whole spin state can invert back and forth several times during a calculation and a very small average magnetization can sometimes be calculated even though most of the time it is almost \(+1\) or \(-1\).

Q12 2D spin lattice#

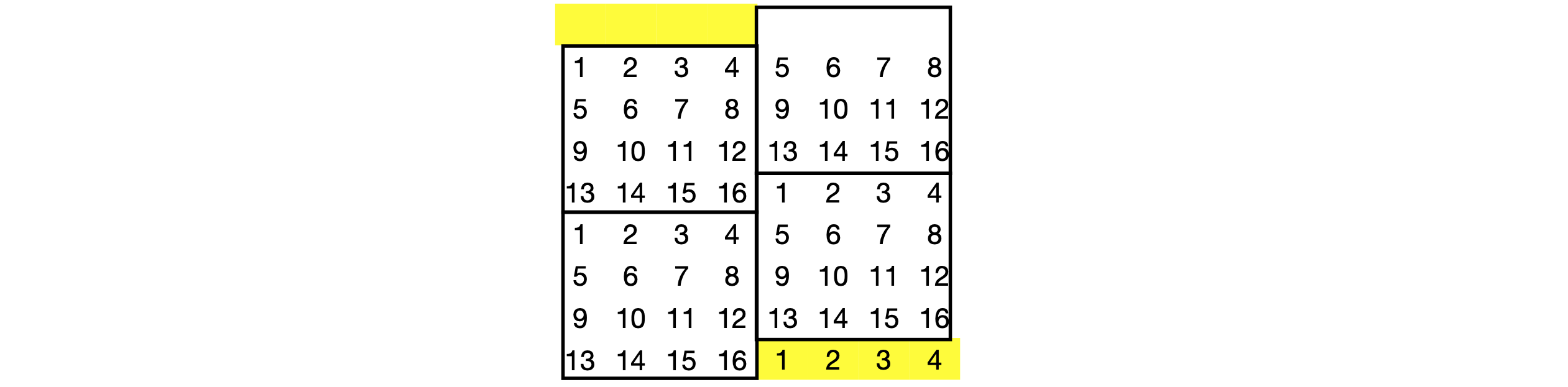

The two-dimensional lattice can be represented as an array of spins labelled from \(0 \to n\), rather than as a two-dimensional array as in the example. If helical boundary conditions are applied, see Figure 20, then a saving in computer time can be achieved. Rewrite the algorithm to use a linear array to hold the spin state, and use helical boundary conditions.

Figure 17. Showing how helical boundary conditions are applied.

Q13 Random walk & Diffusion#

Modify the random walk diffusion example to produce a graph similar to that shown in the left panel of Figure 10, but only for one walk at a time of length \(50\), starting at position \(0\).

Strategy: This is a simpler calculation than in the example; the value of \(m\) the present position of the walker at a point in the calculation is stored in a new array and then this is plotted. The array xdata and the repeat loop, ‘for L ‘ are not needed. The graph scale should be adjusted to see the data properly.

Q14 Photon counting#

In a time-resolved, single-photon counting experiment (TRSPC), the time between excitation and the first photon to be detected, is measured by a time-to-amplitude converter (TAC). This works by charging a capacitor linearly in time; the charging is started before the excitation photon reaches the sample and stops when a fluorescence photon is detected by a photomultiplier or similar detector capable of detecting single photons. Besides the fixed dead time of the electronic circuitry, the time lag measured is the time a molecule remains in the excited state.

Simulate the arrival time of,say, \(500\) photons, each one from a different excitation of the sample and plot a graph of the number of events on the x-axis and their arrival times on the y-axis. Assume that the molecule has a 10 ns lifetime. A plot similar to that of Figure 11 should result.

Strategy: This question is somewhat ‘dressed up’ but is quite straightforward. Repeatedly use the equation \(t = -\tau \ln(r)\) , equation 13, to estimate times, and plot \(t\) vs the number of the event. The number of molecules is 1 in each case because only one photon is detected each time, and the number of events is \(500\). It is easier to work in units of nanoseconds, so make the lifetime 10. Remember to label the graph as time/ns.

Q15 Electron transfer in DNA#

A dye molecule D is intercalated into DNA and, when electronically excited, undergoes electron transfer, which competes with fluorescence and decreases the state’s lifetime. Typically, D might be methylene blue whose excited state is oxidized by receiving an electron although only from a guanine base (G) and not from bases A, T, or C because their redox potential will not allow this to occur at a rate that will compete with fluorescence. The position that the dye intercalates is random, as is the DNA sequence; for example, one of possibly \(4^{10}\) arrangements with \(10\) base pairs could be

The electron transfer rate constant depends exponentially on distance as

and, therefore, the G base does not have to be next to the dye to be quenched; \(\beta\) is a constant that depends on the overlap of the electronic orbitals of the donor and acceptor molecules.

(a) Calculate the rate of electron transfer, and the measured fluorescence decay profile of the dye in the presence of electron transfer. The isolated excited state of the molecule has a \(380\) ps lifetime, or rate \(k_f = 10^{12}/380 \mathrm{s^{-1}}\). The constant \(k_0 = 3.0\cdot 10^{12}\mathrm{s^{-1}}\) and \(\beta = 7.0 \mathrm{nm^{-1}}\). In DNA, the distance between base pairs is \(0.34\) nm and this is also the separation of the dye to its nearest base. Assume that all bases are present in equal amounts and make the calculation cover a distance of \(5\) base pairs either side of the dye. Calculate the decay over \(1000\) ps and use \(1\) ps bins to form a histogram, and when the code is working, repeat the calculation \(50000\) times.

(b) Show that as \(\beta\) is reduced more quenching of the excited state occurs. Explain why this is.

Strategy: This problem looks as though it could be solved by writing down the rate equation. Only one dye is ever present in each piece of DNA and so the rate equation has the form

if a base G is at position \(3\) and \(6\). The rate constant at position 3 away from the dye is, for example, \(k = k_0e^{-3\times 0.34\beta}\). However, a little reflection will tell you that there are many different positions for G relative to the dye, and a variable number of G’s may also be present. If there are \(10\) base pairs, then there are \(4^{10} = 1048576\) possible ways of arranging the bases, which is a huge number of equations to solve. Instead, the decay rate constant can be estimated by the Monte Carlo method, by placing the G bases at random positions about the dye and repeating the calculation a few thousand times until the result is effectively constant. The decay of the dye is expected to be non-exponential, as previously shown in the problem of donors and acceptors at random, in solution.

Q16 SIR model of disease#

One simple model of disease spreading is the S-I-R model, meaning individuals are Susceptible, Infected, or Removed. The scheme is

The differential equations can solved numerically as described in Chapter 11 and also by Monte Carlo integration, see Section 2.2. Instead of these approaches, a discrete Monte Carlo simulation will be used to describe how a disease is transmitted and which does not involve integrating the differential equations.

Suppose that just one student becomes infected with flu and then transmits his infection to others; some older students have already had the infection and are immune, while all the others are susceptible to catching it. If there are 1000 students and each day 1 person at random can become infected, provided they are not immune, calculate;

(a) The number infected, and the number susceptible day by day for a period of 40 days. Assume that \(1\)% are initially immune and that each student has a probability of \(0.2\) of recovering each day after being infected. Calculate also the size of the epidemic, which is the number in the removed category.

(b) Repeat the calculation with different fractions of immunized persons and rationalize your results.

(c) In some diseases, such as colds and influenza, after becoming infected a person is again susceptible; a minor change to the algorithm allows for this. Show that the infection persists.

Strategy: There are three types of students; immunized, susceptible, and infected. Initially, one student is infected out of \(1000\) students. The calculation can be set up by choosing, at random, \(10\) students, which is \(1\)% of the total to represent the immune students and then one more of those who are not immune to be the initially infected student. To do this, an array is defined to represent the state of each student and which contains integer values to represent one of the three states; for example, 2 = infected, 1 = susceptible, and 0 = immune. The number infected is found by summing up all those members of the array with a value of 2. The progress of time is represented by a for loop from \(1 \to 40\). The calculation should be repeated to average a number of initial distributions of infected and immune persons.

The method is

(1) Define constants and parameters, number of students and so forth.

(2) Choose at random those to be immune and one to be infected initially; do not choose anyone that is immune.

(3) Make one ‘for’ loop over the number of repeat calculations; inside this, make a second ‘for’ loop to range over the number of students. In this latter loop

\(\quad\)(i) If an infected student is found, choose two more at random and infect them if they are not already immune. This is the first step \(S \to I\) and depends on both S and I and the rate constant \(k_2\) per day.

\(\quad\)(ii) Choose a random number in the range \(0 \to 1\), and if less than the chance of recovery, choose a student at random and if already infected, make immune. This is the removal step with rate constant \(0.2\)/day, and depends only on those infected.

\(\quad\)(iii) End the loop over the number of students.

(4) Add up the number of students infected and store the results.

(5) End the repeat loop.

Q17 Autocatalytic reaction#

Modify the algorithm in the autocatalytic reaction example (or fire spreading) to include the four nearest diagonal points as well as those along the same row and column. The relative rate should be \(50\)%, at a fraction \(0.5694\) if a large grid is chosen. Allow trees to burn out during each cycle, so becoming gaps, and calculate the number burning as a fraction. Then do similar calculations on a triangular or hexagonal lattice, which is harder.