Solutions Q 93-114

Contents

Solutions Q 93-114#

# import all python add-ons etc that will be needed later on

%matplotlib inline

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from sympy import *

init_printing() # allows printing of SymPy results in typeset maths format

plt.rcParams.update({'font.size': 14}) # set font size for plots

Q93 answer#

Differentiating with respect to \(x\) first

and then with \(y\) gives

and where brackets are not around the derivatives, for example with \(\displaystyle \frac{\partial z}{\partial x}\), there is no ambiguity because \(y\) must be constant.

The mixed derivative does need us to specify which variable is held constant,

which can be simplified somewhat. Using SymPy the mixed calculation can be done in one step

z, x, y = symbols('z, x, y')

z = (x**2 + y**2)*sin(y/x)

simplify(diff(z,x,y) )

Q94 answer#

(a) Differentiating with \(x\) twice produces \(\displaystyle \frac{\partial z}{\partial x}=e^{x+cy}+\frac{1}{x-cy} \quad \text{ and }\quad \frac{\partial^2 z}{\partial x^2}=e^{x+cy}-\frac{1}{(x-cy)^2} \)

and with \(y\) also \(\displaystyle \frac{\partial z}{\partial y}=ce^{x+cy}-\frac{1}{x-cy} \quad \text{ and }\quad \frac{\partial^2 z}{\partial x^2}=c^2e^{x+cy}-\frac{1}{(x-cy)^2} \)

Multiplying the second derivative in \(x\) by \(c^2\) shows that \(z\) is a solution to \(\displaystyle \frac{\partial^2z}{\partial y^2}=c^2\frac{\partial^2z}{\partial x^2}\)

(b) By ‘arbitrary’ is meant only that we need not specify exactly how \(z\) depends on \(x\) and \(y\) except that they contain terms in \(x + cy\). Taking derivatives;

and

then by comparing the second derivative in \(y\) with that in \(x\) multiplied by \(c^2\) shows again that \(\displaystyle \frac{\partial^2z}{\partial y^2}=c^2\frac{\partial^2z}{\partial x^2}\).

Q95 answer#

(a) By substitution \(\displaystyle \frac{\partial c}{\partial t}=-\frac{\partial J}{\partial x}=-\frac{\partial}{\partial x}\left(-D \frac{\partial c}{\partial x} \right)\), therefore \(\displaystyle \frac{\partial c}{\partial t}=D\frac{\partial^2 c}{\partial x^2}\) which is Fick’s second law.

(b) While the complete expression for \(c\) can be differentiated, it is easier to remove the constants and simplify the expression first. Doing this produces

differentiating and simplifying gives

To differentiate twice with \(x\) gives

which proves that the equation for \(c\) is a solution to Fick’s Second Law as this result is the same as the previous one. Using SymPy we can check the result easily. (it is necessary to use the simplify command to force the simplification.)

x, D, c0, t = symbols('x, D, c0, t')

f= c0/sqrt(4*pi*D*t)*exp(-x**2/(4*D*t))

if simplify((D*diff(f,x,x) - diff( f,t))) == 0:

print('true')

else:

print('false')

true

(c) The concentration equation does not apply at \(t = 0\) because here \(c\) is infinity and this is not possible as the total concentration is \(c_0\) unless the disc of atoms is made infinitesimally thin. In solving the diffusion equations, the complete answer has been approximated and so simplified to obtain the concentration equation quoted above. At \(t = 0\) the total concentration must be \(c_0\) which is the same at all times because no material is lost.

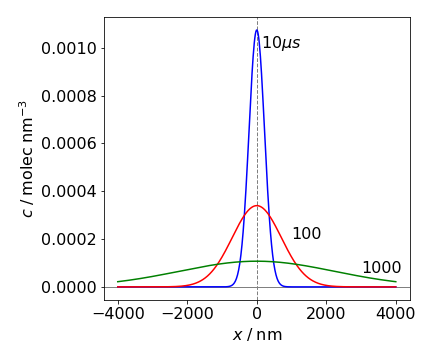

(d) As \(x= \sqrt{2Dt}\) and if \(t = 1\,\mathrm{\mu s}\) then \(x \approx 4.5 \cdot 10^{-7}\) m so a scale of microseconds and tens to hundreds of nanometres seems sensible to try. A concentration of \(1\,\mathrm{ mol\,dm^{-3}} =0.602\) in molecules / nm\(^3\) . Plotting produced the following graph, which shows how the molecules all initially at \(x = 0\) at \(t = 0\), spread out into the solution as time progresses and shows that diffusion really is a slow process. When you notice the smell of coffee or perfume in a room this is probably due to convection of the air rather than diffusion.

Figure 63 One-dimensional diffusion of molecules initially placed at \(x = 0\) at \(t = 0\) is shown at different times in microseconds. The diffusion constant is the similar to that of water, \(\approx 2.5\cdot 10^{-9}\,\mathrm{ m^2\,s^{-1}}\). At time zero, the molecules form a \(\delta\) function at \(x = 0\).

Q96 answer#

(a) Expanding \(\displaystyle \left(p+\frac{a}{V^2} \right)(V-b)=RT\) produces \(pV+a/V-bp-ab/V^2=RT\).

At constant \(T\) and because \(p\) is a function of \(V\)

the first derivative wrt \(V\) is

Simplifying produces \(\displaystyle (V-b)\left( \frac{\partial p}{\partial V}\right)_T + p -\frac{a}{V^2}+\frac{2ab}{V^3} = 0\).

Labelling with a subscript \(c\) to indicate the critical points, and because the derivatives are zero here, produces \(\displaystyle p_c-\frac{a}{V_c^2}+\frac{2ab}{V_c^3}=0\).

(b) Starting with the first derivative the second is, at constant \(T\),

and as these derivatives are also zero at the critical point \(V_c=3b\). Substituting into the equations for \(p_c\) produces \(\displaystyle p_c=\frac{a}{27b^2}\) and \(T_c\) can be found by substitution into the van-der Waals equation and is \(\displaystyle T_c=\frac{8a}{27bR}\).

Doing the same calculation in a different way with SymPy gives

a, b, R, T, p, V = symbols(' a, b, R, T, p, V')

pvdw = R*T/(V - b) - a/V**2 # pressure in vdw equation

dpdv = diff(pvdw,V) # dpdV

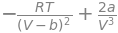

dpdv

dpdv2 = diff(pvdw,V,V) # d^2pdV^2

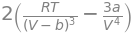

dpdv2

ans = solve( (dpdv, dpdv2),(T, V) ) # answer solving simultanoeus eqns gives T and V in that order

ans

Q97 answer#

Differentiating \(H\) with temperature at constant pressure \(p\) produces \(\displaystyle \left( \frac{\partial H}{\partial T}\right)_p = \left( \frac{\partial U}{\partial T}\right)_p +p \left( \frac{\partial V}{\partial T}\right)_p\)

and from the definition of \(C_p\) and rearranging gives the required expression \(\displaystyle \left( \frac{\partial U}{\partial T}\right)_p=C_p - p \left( \frac{\partial V}{\partial T}\right)_p\)

Q98 answer#

At constant pressure, differentiating \(S\) with \(T\) produces \(\displaystyle \left( \frac{\partial S}{\partial T}\right)_p= n\frac{C_p}{T}\).

Because volume is not explicitly in the equation, the ideal gas law is used to substitute for pressure and so obtain an equation containing volume;

then

which by substitution of the first result shows that the two partial derivatives are different;

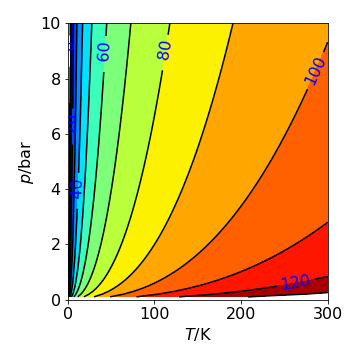

The plot shows this also as the partial derivatives are horizontal or vertical lines on this plot and are clearly different. For example at constant pressure, say \(2.5\) bar the slope at low temperatures is greater than at higher ones as the contours become more widely spaced at the temperature increases, this is in accord with \(\displaystyle \left( \frac{\partial S}{\partial T}\right)_p= n\frac{C_p}{T}\). In the plot \(C_p= 5R/2\) which is that for a diatomic molecule; \(3R/3\) for translation and \(R/2\) each for vibrational kinetic and potential energy.

Figure 64. Contour plot of the entropy with pressure and temperature. (\(C_p=5R/2\) and \(S_0=0\)). The contours are at constant entropy with values labelled in J/mol/K. The gradient \(\partial S/\partial p\) at constant \(T\) would be a vertical line, \(\partial S/\partial T\) at constant \(p\) is a horizontal line.

Q99 answer#

(a) Using the ideal gas law \(pV=RT\) therefore \(\displaystyle \left( \frac{\partial p}{\partial T}\right)_V=\frac{R}{V}\) and therefore \(\displaystyle \left( \frac{\partial U}{\partial V}\right)_T=\frac{RT}{V}-p=0\). This result is expected because the ideal gas is defined as consisting of hard sphere point molecules with no interaction energy between them; therefore, at constant temperature, the internal energy does not depend upon the volume of the gas.

(b) The van der Waals gas is defined by \(\displaystyle \left(p+\frac{a}{V^2} \right)(V-b)=RT\). With \(V\) as a constant a \(\displaystyle \left( \frac{\partial p}{\partial T} \right)_V =\frac{R}{V-b}\) . Using the equation in the question

and the van der Waals equation was used to simplify the derivative. This confirms that the constant \(a\) is related to the interaction energy between molecules; the internal energy becomes large when the volume is small. Conversely, when the volume is large,

because the molecules rarely meet one another and the gas becomes ‘ideal’.

Q100 answer#

(a) As \(pV=nRT\) and \(T\) is held constant in an isothermal process then \(\displaystyle \left( \frac{\partial V}{\partial p} \right)_T =-\frac{nRT}{p^2}\).

Substituting for \(RT\) and dividing by \(-V\) gives

(b) For the van der Waals gas where \(\displaystyle \left(p+\frac{a}{V^2} \right)(V-b)=RT\) expanding the terms to make it easier to differentiate gives

Differentiating \(V\) wrt \(p\) at constant \(T\) gives

and after some serious rearranging

As a check if \(a\) and \(b\) are both zero then the result for an ideal gas results; \(\kappa = 1/p\).

Q101 answer#

(a) When \(t = 0\) the concentration is \(\displaystyle c=c_0e^{v(x-x_0)/2D}\).

If also \(x = x_0\) then the concentration is \(c_0\) at zero time, and this is therefore the initial concentration and \(x_0\) is therefore the initial position. Clearly, the units of each term in the equation must be the same. On the left-hand side they are \(\mathrm{dm^3\, mol^{-1}\,s^{-1}}\), and the first term on the right is \(D\partial^2 c/\partial x^2\) which has units \(D \cdot\,\mathrm{ dm^3\, mol^{-1}\, dm^{-2}}\). To make this \(\mathrm{dm^3\, mol^{-1}\,s^{-1}}\), \(D\) must have units of \(\mathrm{dm^2\, s^{-1}}\) or distance\(\mathrm{^2\, time^{-1}}\) (or area/time). In solution, large molecules typically have diffusion coefficients of \(\approx 10^{-9}\,\mathrm{ m^2\, s^{-1}}\).

(b) To show that the equation in the question is a solution, differentiate with respect to \(t\) and \(x\). Differentiation with respect to \(t\) gives

and wrt \(x\);

and

Looking at these three derivatives the exponential terms are the same in each and when the diffusion equation is formed they will all cancel out. Therefore

which is zero, proving what was required.

Q102 answer#

(a) The first law of thermodynamics states that,for an infinitesimal quasi-statical change of state, a condition often called ‘reversible’, the change in the internal energy \(U\) of an object is the sum of the heat transferred to the object \(Q\) and the work done on the object \(W\),

The work done on a gas is \(-pdV\) and because \(U=U(T)\) is a function of temperature only for an ideal gas, then we can state that \(\displaystyle dU=\frac{dU}{dT}dT\) and write \(dU\) rather than \(\partial U\), because \(U\) only depends on \(T\) and therefore cannot be a partial derivative of anything else.

Do not be tempted to differentiate the first law; it is already in differential form. Substituting for \(dU\) into the first law equation and rearranging produces

The heat capacity of a substance is defined as the heat absorbed per unit change in temperature, thus

and working under conditions of constant volume means that \(dV\) is zero and

The constant volume heat capacity is therefore \(\displaystyle C_V=\frac{dU}{dT}\).

Next, to calculate the constant pressure heat capacity \(C_p\), the change in pressure must be zero, therefore \(dp \to 0\). To do this the first law must be recast in terms of \(dp\), rather than \(dV\). From the ideal gas law \(pV = RT\) and for changes in pressure, temperature and volume; \(pdV+Vdp=RdT\). Substituting for \(pdV\) into the first law produces

and so it follows that at constant pressure when \(dp \to 0\),

and therefore as \(\displaystyle \frac{dQ}{dT}\) defines heat capacity \(\displaystyle C_p=\frac{dU}{dT}+R\) and \(C_p=C_V+R\).

The heat capacity at constant pressure is larger than at constant volume because the volume must change if the pressure is constant and therefore work has to be done on the gas to make it expand.

(b) A new function called the enthalpy is always used to take account of any change in volume (and hence work) that occurs at constant pressure and is defined as

For 1 mole of gas, \(n = 1\); differentiating \(H\) with respect to \(T\) at constant \(p\) produces

and by comparison with the previous definition it follows that

This is usually written as \(\displaystyle C_P=\frac{d H}{d T} \) because the constant \(p\) is implied with \(C_p\).

Q103 answer#

(a) The quantities \(dU\) and \(dS\) are both functions of \(T\) and \(V\), and starting with \(U\) the total derivative is,

and similarly

Substituting for \(dU\) into the equation given in the question to obtain,

and rearranging for \(dS\) gives

Comparing with the definition of \(dS\) in the total derivative, the \(dV\) term is

and the \(dT\) term

from which, using the definition of \(C_V\) in the previous question, we obtain

(b) As \(H\) is by definition \(H=U+pV \) and therefore a function of \(U\), \(p\), and \(V\), then by definition

Substituting for \(dU + pdV\) into the equation given in the question, \(dU + pdV = TdS\), gives \(dH = TdS + Vdp\). As \(H\) and \(S\) are each a function of \(T\) and \(p\), the total derivatives are

Next substituting \(dH\) into \(dH = TdS + Vdp\) and rearranging gives

and comparing terms with \(dP\) and then \(dT\) and using

therefore \(\displaystyle \left( \frac{\partial S}{\partial T}\right)_p=\frac{C_p}{T}\).

To find the entropy this equation has to be integrated,

which produces \(S=S_0+C_p\ln(T)\) and assuming that \(C_p\) is independent of temperature over the range of temperatures studied and \(S_0\) is an integration constant.

Q104 answer#

Equation(50) states that \(\displaystyle\left( \frac{\partial U}{\partial V}\right)_T=T\left( \frac{\partial p}{\partial T}\right)_V-p\)

and as the van der Waals equation is \(\displaystyle \left(p+\frac{a}{V^2}\right)(V-b)=RT\), differentiating pressure wrt \(T\) gives

therefore \(\displaystyle\left( \frac{\partial U}{\partial V}\right)_T=\frac{a}{V^2}\).

Q105 answer#

Volume has the general form \(V=f(p,V,E)\) and because \(E\) is stated to be constant, its derivative is zero, giving

see equation 42. Dividing this through by \(dT\) at constant \(E\) produces

Q106 answer#

Rewriting to isolate \(V\) gives \(V=RT/p+B_T\) and differentiating produces

The mixed derivatives are the same

showing that they are perfect differentials.

Q107 answer#

By integrating the Maxwell equation, the entropy change between any two pressures \(p_0\) and \(p_1\) is

(a) Expanding the van der Waals equation of state \((p+a/V^2)(V-b)=RT\) gives

Differentiating \(V\) with respect to \(T\) with \(p\) constant and rearranging gives

The entropy is obtained by substituting for the derivative, forming an integral with a standard logarithmic form; for example, see Integration 2.3.

The similar calculation for the ideal gas gives

and by subtracting this entropy from that of the vdW gas makes the change in entropy from 1 to \(p\) bar

This reduces to that of the ideal gas when both \(a\) and \(b\) are zero. This result can be written in terms of volume alone by substitution

The units inside the log have dimensions of pressure. These must be made dimensionless by dividing by 1 bar, although this is almost never shown in a formula.

(b) The Bertholet equation can be simplified

where \(c_0, c_1\) are constants as may be seen by comparison with the equation in the question. The derivative is

The change in entropy is, following the method in (a)

making

as the difference in entropy from 1 to \(p\) bar. The equation is dimensionally correct; in the second term the temperature units cancel as do the pressure, leaving only \(R\). The pressure should be represented as \(p\)/bar.

Q108 answer#

(a) Differentiating \(dH=TdS+Vdp\) with \(p\) at constant \(T\) changes the differentials into partial ones and gives

Substituting for the entropy term produces the required equation \(\displaystyle \left( \frac{\partial H }{\partial p} \right)_T =-T \left( \frac{\partial V}{\partial T} \right)_p+V\).

(b) Differentiating each term with temperature at constant pressure gives

Using the definition \(C_p = dH/dT \equiv (\partial H/\partial T)_p\) the left-hand side is simplified and also cancelling terms on the right gives

Integrating this equation produces

which means that the heat capacity relative to a standard state at \(p\) = 0 and at temperature \(T\) is found by integrating the second derivative of the change in volume of the gas with temperature over a range of pressures from 0 to \(p_1\). This change is zero for an ideal or van der Waals gas but not for the Berthelot gas where from the previous question

and

making

Note that the right-hand side of this equation has dimensions of energy/temperature, as does the heat capacity.

Q109 answer#

(a) by definition, \(\displaystyle C_V=\left( \frac{\partial U}{\partial T} \right)_V\) and also as \(H=U+pV\), and by definition

it follows that

at constant pressure.

(b) Comparing the equations for \(C_p\) in parts (a) and (b) it seems that the derivative \(\partial V/\partial T\) at constant pressure will be needed, so we start with this. The internal energy is a function \(U = f(p, V, T)\), and therefore can produce the differential

which by dividing by \(dT\) at constant pressure gives

The first term on the right is \(C_V\) which leaves \((\partial U/\partial T)_p\) to be found. As \(U=H-pV\) then

and by dividing by \(dT\) at constant \(p\) produces,

Substituting for \((\partial U/\partial T)_P\) gives the final expression

which reduces to \(C_p=C_V+R\) for an ideal gas.

Q110 answer#

Differentiating the entropy and multiplying by \(T\) produces \(\displaystyle TdS=T\left( \frac{\partial S }{\partial T} \right)_VdT+T\left( \frac{\partial S}{\partial V} \right)_TdV\).

By substituting Maxwell’s equation

The first term has now to be examined. The heat capacity \(C_V\) is the rate of change of internal energy with temperature \(C_V = (\partial U/\partial T)_V\) and entropy \(S = U/T\) giving \(C_V = T(\partial S/\partial T)_V\) which by substitution gives the final result,

Q 111 answer#

(a) Differentiating the Helmholtz energy gives \(\displaystyle \left( \frac{\partial A}{\partial V} \right)_T=\left( \frac{\partial U}{\partial V} \right)_T-T\left( \frac{\partial S}{\partial V} \right)_T\).

Next the derivatives need to be changed into terms that can be measured, which means those involving \(T\) and \(p\). With this in mind using the differential form \(dA = \cdots\) The first derivative is

and because \(dA\) is a perfect differential, the derivative in \(S\) becomes

and the rate of change of internal energy

The van der Waals equation can now be used directly giving

and the final result is \(\displaystyle \left( \frac{\partial U}{\partial V} \right)_T=a\frac{n^2}{V^2}\).

(b) The constant \(a\) for CO\(_2\) is \(3.66\,\mathrm{ bar\, dm^6\,mol^{-2}}\). Integrating the last result gives

which has units \(\mathrm{bar dm^3\,mol^{-1}}\). As pressure (bar) is force/area therefore the units are \(\displaystyle \mathrm{\frac{kg\cdot m\cdot s^{-2}}{m^2}m^3=\frac{kg\cdot m^2}{s^2}=J}\). The change in internal energy of \(1\) mole of CO\(_2\) expanding from \(10 \to 20\,\mathrm{ dm^3}\) at constant temperature is therefore \(0.183\) J.

Q112 answer#

(a) The integral is \(\displaystyle \int\left(\frac{\partial U}{\partial V} \right)_TdV=\int\left[ T\left( \frac{\partial S}{\partial V} \right)_T-p \right]dV\)

and this can be put in a more useful form with the Maxwell equation for \(S\) and \(V\) given in Q110 and then

Differentiating the (van der Waals) pressure wrt \(T\), simplifying the result and integrating gives

(b) The total energy is

where the first term is the kinetic energy obtained by using the eqi-partition theorem and is in effect the internal energy if chlorine is assumed to be an ideal gas.

Q113 answer#

Rewriting gives \(\displaystyle \ln(k)=\ln(A)-\frac{\Delta H}{RT}+\frac{\Delta S}{R} \) and differentiating at constant pressure

Substituting the identity in the question and rearranging produces \(\displaystyle \left(\frac{\partial k }{\partial T} \right)_p=k\left[ \frac{1}{A}\left(\frac{\partial A }{\partial T} \right)_p+\frac{\Delta H}{RT^2} \right]\).

Q114 answer#

(a) The partial derivative can be expressed directly as

The derivatives in \(x\) are calculated using a right-angled triangle to obtain angles (see Q12 & fig 38),

and as \(\theta =\tan^{-1}(y/x)\)

and these can be substituted into the result if required.

(b) The second derivative is harder to evaluate. Start by differentiating the last result as if the whole of it were \(z\), i.e.

Using the product rule and operating to the right using \(\partial \partial r\) the first term becomes

and we used

in the second term. The second term is

Finally, notice that all the terms are derivatives between the two coordinates except two of them, which have \(\partial ^2\theta/\partial r\partial x\) and \(\partial^2r/\partial \theta \partial x\) and these are zero because \(r\) and \(\theta\) are only functions of \(x\) and \(y\) and a derivative with respect to anything else would be zero. The result is

The second derivatives in \(r, x \theta\) are

substituting and rearranging gives the result