Solutions Q8 - 12

Contents

Solutions Q8 - 12#

# import all python add-ons etc that will be needed later on

%matplotlib inline

import numpy as np

from numpy import linalg as LA

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from sympy import *

init_printing() # allows printing of SymPy results in typeset maths format

plt.rcParams.update({'font.size': 16}) # set font size for plots

Q8 answer#

(a) \(\langle s|s\rangle\); the left-hand icon is the bra, which is, in quantum mechanics, always the transpose and complex conjugate of the ket. (These two combined operations are called the Hermitian adjoint.) In this question, the entry in the matrix is a number so its conjugate is still 1. The result of any calculation of the form bra : ket or \(\langle \cdots|\cdots \rangle\) is the dot or inner product,

similarly \(\langle p_x|p_x\rangle =\langle p_y|p_y\rangle=1\) and in each case show that the basis set if normalised.

shows that the basis set is also orthogonal. These results, normalization and orthogonality, mean that the basis set is orthonormal.

(b) The calculation the other way around is ket-bra or \(|\cdots\rangle\langle\cdots|\) and will always produce a matrix.

(i) \(\displaystyle |s\rangle \langle s|=\begin{bmatrix}1 \\ 0 \\ 0\end{bmatrix}\begin{bmatrix}[1 & 0 & 0\end{bmatrix}=\begin{bmatrix}1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0&0&0\\0&0&0 \end{bmatrix}\)

The vectors are commensurate because the row / column order is \(3 \times 1\) and \(1 \times 3\) producing a \(3 \times 3\) matrix. The related calculation for the other components of the basis set produce

As each of the matrices is zero for all but one component, these operators will, when right multiplied by a ket, extract just one coefficient and produce a new ket. For example

(ii) \(|s\rangle \langle p_x| =\begin{bmatrix}1\\0\\0\end{bmatrix}\begin{bmatrix}0&1&0\end{bmatrix}=\begin{bmatrix}0 & 1 & 0 \\ 0&0&0\\0&0&0 \end{bmatrix}\)

The similar calculation with bra \(\langle s|\) and\(\langle p|\) produce related matrices with unity in the top row and in the first and third column respectively.

(iii) Now operate using the matrix \(|s\rangle \langle s|\) ,on \(|\varphi\rangle\) .Expanding using the result from (i) gives

which is a new ket, \(b_s|s\rangle\) and therefore the result of an experiment operating on \(|\varphi\rangle\), which is a linear superposition state, is to collapse the wavefunction \(\varphi\) and produce the amount \(b_s\) of the state \(| s \rangle\).

(iv) The effect of basis bra \(\langle p_y|\) is to select only the \(y\) component,

(vii) A matrix operator results; notice the row / column pattern of multiplication,

Q9 answer#

Using the definition of the bra-ket, the right hand bra- ket is obtained by taking the complex conjugate of both vectors and noting that for any complex number \(z\), taking the complex conjugate twice leaves it unchanged, \(z = (z^*)^*\). Starting with the right hand side

and the left hand side of the expression has the bra and ket reversed;

which is the same result so that \(\langle\psi|\varphi\rangle =\langle\varphi|\psi\rangle^*\), and this is general because \(c\) and \(b\) are arbitrary constants. By induction, this result would be true no matter how long the vectors were.

Q10 answer#

(a) Starting with each component and making the square of the operator as the product,

next, remembering that \(i^2 = -1\) we find that

then, adding terms, produces the result \(\displaystyle \pmb{I}^2=\frac{3\hbar^2}{4}\pmb{1}\) where \(\pmb{1}\) is the unit diagonal matrix.

(b) The commutator of two matrices A and B is \([\pmb{A}, \pmb{B}] = \pmb{A}\pmb{B} - \pmb{B}\pmb{A}\). In this example,

Because the two operators \(\pmb{I}^2\) and \(\pmb{I}_z\) both satisfy the Schroedinger equation by producing eigenvalues, and because they commute with one another, it is possible to determine the \(\pmb{I}^2\) and \(\pmb{I}_z\) angular momenta simultaneously. The commutator of the \(x, y, z\) components is

and as this is not zero, the angular momentum components do not commute. This is true in any order of \(x, y\) or \(z\), so it is not possible to determine simultaneously the \(x\) or \(y\) components of the angular momentum when \(\pmb{I}_z\) and \(\pmb{I}^2\) are determined. This is a consequence of the uncertainty principle.

(c) Operating on \(\alpha\) with \(\pmb{I}^2\) gives

A similar calculation leads to \(\displaystyle \pmb{I}^2α =\frac{3\hbar^2}{4}\alpha\).

The operator \(\pmb{I}^2\) is a Hamiltonian operator, because it has the form \(H\psi=c\psi\) where\(c\) is a constant. In this case \(\pmb{I}^2\beta=c\beta\) and \(\pmb{I}^2\alpha=c\alpha\) where \(c=4\hbar^2/4\). The magnitude of the angular momentum is \(\sqrt{3\hbar^2/4}\).

Operating on the \(z\) component of the spin angular momentum produces

with eigenvalue of \(\hbar/2\)

with eigenvalue \(-\hbar/2\).

(d) The \(x,y\) and \(z\) components are calculated in a similar way;

but the results how that an eigenstate has not been produced because \(\pmb{I}_x\alpha \ne c\alpha\) where \(c\) is a constant. With the \(\beta\) spin state the effect is similar

With the \(y\) component, again the eigenstate is not produced.

(e) The raising operator \(\pmb{I}^+ = \pmb{I}_x + i\pmb{I}_y\) has the following effect on state \(\alpha\);

and as \(\alpha\) is the highest state it cannot be raised any higher. The effect on state \(\beta\) is to raise it to state \(\alpha\) as follows,

Similarly, lowering operators lower \(\alpha\) to \(\beta\) and will not lower \(\beta\) any further.

Q11 answer#

(a) If the basis is represented as a set of matrices such as

where the position of the number 1 in the vector is the position of quantum number \(m\) in the basis set. Any two similar vectors are normalized and any two different vectors are zero, thus the bra-ket \(\langle Lm|Lm\rangle = 1\) but \(\langle Lm|Ln \rangle = 0\) when \(m \ne n\).

(b) A matrix is set up with the basis set ordering. Because only the \(m\) values change, the set can be approximated as \(-3/2, -1/2, 1/2, 3/2\) and \(L\) does not need to be listed. The \(\pmb{L}^+\) operator only couples states with \(m\) and \(m + 1\); only the states \(-3/2 \to -1/2; -1/2 \to 1/2\) and \(1/2 \to 3/2\) are coupled, thus the \(4 \times 4\) matrix has only three non-zero terms and these are each one place to the right of the diagonal with the ordering used.

The matrix entries have values:

row 2, col 1: \(-3/2 \to -1/2\) is \(\displaystyle \sqrt{\frac{15}{4}-\frac{-3}{2}\frac{-1}{2} }=\sqrt{3}\)

row 3, col 2: \(-1/2 \to -1/2\) is \(\displaystyle \sqrt{\frac{15}{4}-\frac{-1}{2}\frac{-1}{2} }=2\)

row 4, col 3: \(1/2 \to 3/2\) is \(\displaystyle \sqrt{\frac{15}{4}-\frac{1}{2}\frac{3}{2} }=\sqrt{3}\)

making the \(\pmb{L}^+\) matrix

and by a similar argument \(\pmb{L}^-\) is

which is the transpose of \(\pmb{L}^+\).

(c) The \(\pmb{L}_z\) operator has the effect \(\pmb{L}_z |Lm\rangle = m|Lm\rangle\) and as \(m\) has values \(-3/2 \to 3/2\), the operator represented as a matrix is a diagonal matrix in \(m\) values.

The commutator matrix is

which is twice the \(\pmb{I}_z\) matrix as this contains only the \(m\) values.

(d) The calculation is easier if Python/Sympy is used to order and check the terms. Alternatively the method of (a) could be used. The example shows the matrix for a spin of \(3\). \(\pmb{L}^-\) is calculated although it can be found as the transpose of \(\pmb{L}^+\).

L, m, spin, n = symbols('L, m, spin, n')

Iplus = lambda L,m: sqrt(L*(L+1)-m*(m+1))

Iminus= lambda L,m: sqrt(L*(L+1)-m*(m-1))

spin = 3

n = 2*spin + 1

mz = zeros(n,1)

Lplus = zeros(n,n)

Lminus= zeros(n,n)

j = 0

for i in range(-spin,spin+1,1):

mz[j] = i

j = j + 1

pass

for j in range(n):

for i in range(n):

if mz[j] == mz[i] + 1 : Lplus[j,i] = Iplus(spin,mz[i])

if mz[j] == mz[i] - 1 : Lminus[j,i] = Iminus(spin,mz[i])

pass

pass

Lplus

commutator = Lplus * Lminus - Lminus * Lplus # check is 2Lz

commutator

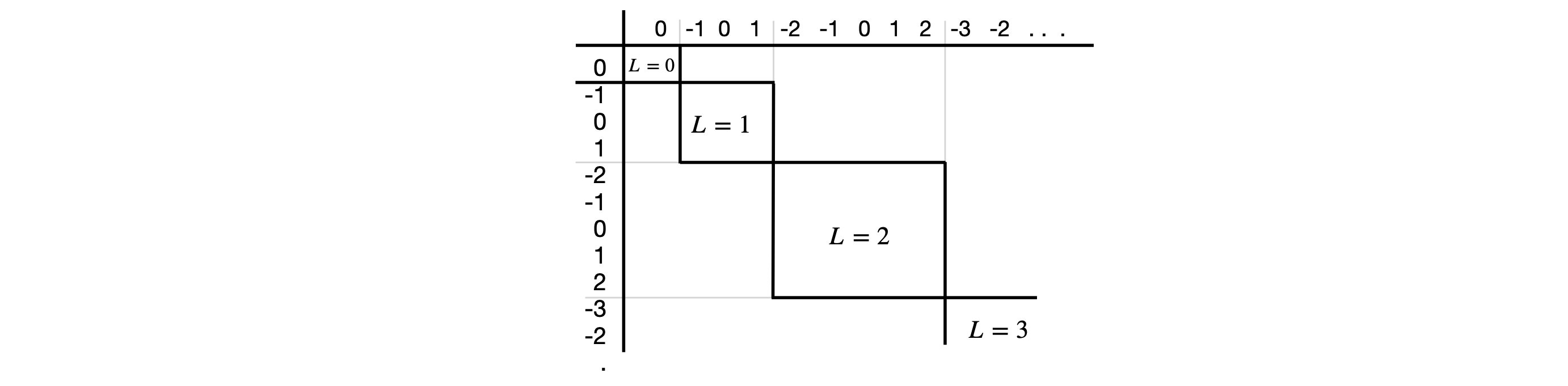

The matrices for the other spins are calculated in the same way. The matrix for all spins is built from these smaller matrices by placing them on the diagonal as shown below for integer spins. All entries outside the block diagonals are zero.

Q12 answer#

(a) Using the definition of the shifting operators

then left multiplying by a bra to increase \(m\) gives

As the basis set is orthogonal and normalized, by definition, \(\langle Lm \pm 1 | Lm\rangle = 0\) and \(\langle Lm + 1 | Lm + 1\rangle = \langle Lm - 1 | Lm - 1\rangle = 1\), therefore

A similar argument works for \(\langle Lm - 1|\pmb{L}_x |Lm\rangle\) and also to obtain the two expressions for \(\pmb{L}_y\).

(b) The commutator is

The effect each operator has is abbreviated as \(\pmb{L}^+ | Lm\rangle \to | Lm + 1\rangle\) meaning that the quantum numbers are increased by one or are decreased by 1; \(\pmb{L}^- |Lm\rangle \to |Lm - 1\rangle \). The effect of two operations is therefore to leave the state unchanged, one raises the other lowers or vice versa. Thus the operation \(\pmb{L}^- (\pmb{L}^+ |Lm\rangle )\to \pmb{L}^- |Lm+1\rangle \to|Lm\rangle\) and similarly for \(\pmb{L}^+ \pmb{L}^-\). Thus, it is established that the product operator has the same effect as \(\pmb{L}_z\) in that the quantum number is unchanged. However, the commutator could turn out to be zero so the square roots have to be worked out. These have the value

which confirms that \([\pmb{L}^+,\pmb{L}^-]=2\pmb{L}_z\).